Youtuber Tesla Bjorn has a great channel reviewing electric cars. Unusually, he tests the range of the cars in a consistent and rigorous way, and posts all his results to a nicely-organized Google Sheet.

One interesting thing I picked up from his channel is that the Porsche Taycan has much worse range than Tesla with its stock tires, but excellent range of 360mi/580km with smaller, more efficient tires (and better weather). One obvious question I had was, how much does tire size and temperature affect range? Since the data was all there, I decided to take a look.

This was also a good excuse to play with brms, a Bayesian multilevel modeling tool for R. I won't explain multilevel modeling here — others have done a much better job at this than I could (see various links below) — but at least in my mind, it's like regular regression, but can incorporate information on subgroups and subgroup relationships. McElreath argues it should just be the default way to do regression, since the downsides are minimal. This blogpost makes a similar case, and helpfully notes that there is evidence that you should generally "use the "maximal" random effects structure supported by the design of the experiment". I take this to mean we should not worry too much about overfitting the model.

Other resources I like include:

- McElreath's Statistical Rethinking book and lectures — also available as brms code.

- Thomas Wiecki and Chris Fonnesbeck running the classic radon measurement example.

- Though not technically multilevel, I think a lot about Andrew Gelman's model of golf putts. It's a great example of modeling a real-life process, and incorporating prior information in a useful way. I wish more science worked like this blogpost...

Bambi vs brms

Even though this exercise was an excuse to try brms, I ended up mostly using Bambi. They are very similar tools, except Bambi is built on Python/PyMC3 and brms is built on R/Stan (pybrms also exists but I could not get it to work). I am assuming Bambi was influenced by brms too.

They both follow very similar syntax to widely-used R regression tools like lme4. Using Bambi also lets me use the excellent Arviz plotting package, and I can still use the more battle-tested brms to confirm my results.

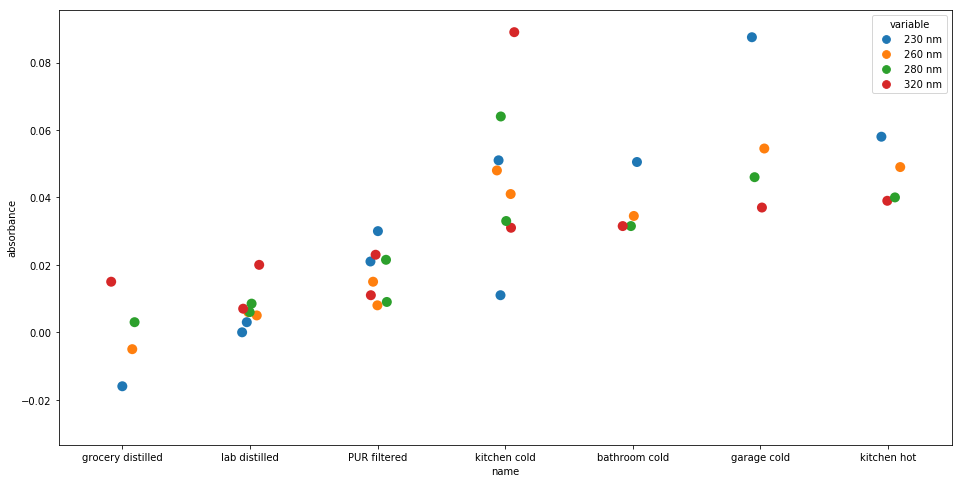

Simulating data

Simulated data is always useful for these models. It really helps get comfortable with the process generating the data, and make sure the model can produce reasonable results under ideal conditions.

My model is an attempt to find the "base efficiency" of each car. Each car has a total tested efficiency, measured in Wh/km, which you can easily calculate based on the range (km) and the battery size (Wh).

In my model, a car's measured Wh/km (Whk) is the sum of effects due to:

- the car's base efficiency (

car) - the weight of the car in tons (

ton) - the ambient temperature (

dgC) - the tire size in inches (

tir) - the surface being wet or dry (

wet) - the tested speed (

spd— Tesla Bjorn tests every vehicle at 90km/h and 120km/h).

The simulated data below match the real data pretty well.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

num_cars = 10

mu_Whk = 100

mu_dgC = 2

mu_wet = 10

mu_tir = 4

mu_spd = 50

mu_wgt = 2

mu_ton = 50

# parameters of each car

has_Whk = np.arange(50, 150, (150-50)/num_cars)

has_ton = np.random.normal(mu_wgt, mu_wgt/5, num_cars).clip(mu_wgt/2)

per_ton = np.random.normal(mu_ton, mu_ton/5, num_cars).clip(mu_ton/5)

per_dgC = np.random.normal(mu_dgC, mu_dgC/5, num_cars).clip(mu_dgC/5) * -1

per_wet = np.random.normal(mu_wet, mu_wet/5, num_cars).clip(mu_wet/5)

per_tir = np.random.normal(mu_tir, mu_tir/5, num_cars).clip(mu_tir/5)

per_spd = np.random.normal(mu_spd, mu_spd/5, num_cars).clip(mu_spd/5)

num_samples = 100

data = []

for _ in range(num_samples):

car = np.random.choice(num_cars)

dgC = np.random.normal(12, 4)

wet = int(np.random.random() > 0.75)

tir = max(0, int(np.random.normal(18,1)) - 16)

for spd in [0, 1]:

Whk = (has_Whk[car] + per_ton[car] * has_ton[car] + per_tir[car] * tir +

(per_spd[car] if spd else 0) + (per_wet[car] if wet else 0))

data.append([f"{car:02d}", has_ton[car], dgC, wet, tir, spd, Whk, has_Whk[car]])

df_sim = pd.DataFrame(data, columns=['car', 'ton', 'dgC', 'wet', 'tir', 'spd', 'Whk', 'has_Whk'])

assert len(set(df_sim.car)) == num_cars, "unlucky sample"

df_sim.to_csv("/tmp/df_ev_range_sim.csv")

df_sim.head()

car ton dgC wet tir spd Whk has_Whk

0 12 2.386572 15.096731 0 2 0 229.106858 110.0

1 12 2.386572 15.096731 0 2 1 293.139807 110.0

2 10 2.083366 12.632114 0 1 0 162.626350 100.0

3 10 2.083366 12.632114 0 1 1 221.408095 100.0

4 19 1.848348 13.203525 0 2 0 256.221089 145.0

Now I can build my model. The model is pretty simple: all priors are just T distributions (a bit fatter-tailed than normal). I originally bounded some of the priors (since e.g., a car cannot use <0 Wh/km), but since I couldn't get that to work with brms, I removed the bounds to make comparisons easier. (The bounds did not materially change the results).

I have an group per car (1|car),

and although I could also have groups for (1|spd) and (1|wet),

I opted not to do that since it didn't change the results,

but made the interpretation a little messier.

I set the intercept to 0 so that the 1|car intercept can represent the base efficiency by itself.

import arviz as az

from bambi import Model, Prior

prior_car = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=100, sigma=50)

prior_ton = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=50, sigma=10)

prior_dgC = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=-1, sigma=1)

prior_wet = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=10, sigma=20)

prior_tir = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=2, sigma=5)

prior_spd = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=50, sigma=20)

model_sim = Model(df_sim)

print(f"{len(df_sim)} samples")

res_sim = model_sim.fit(

'Whk ~ 0 + ton + dgC + tir + spd + wet',

group_specific=["1|car"],

categorical=['car'],

priors = {'car': prior_car, "ton": prior_ton, "dgC": prior_dgC,

"wet": prior_wet, "tir": prior_tir, "spd": prior_spd},

draws=1000, chains=4

)

az.plot_trace(results)

az.summary(res_sim)

The graph below shows that I can recover the base efficiency fairly well, though obviously there are limits to what can be done.

Real data

Now that this all looks good, I can try to model the real data.

import pandas as pd

def get_car(carstr):

if carstr.lower().startswith('model'):

carstr = 'Tesla ' + carstr

if carstr.lower().startswith('tesla'):

return '_'.join(carstr.split(' ')[:3]).replace('-','').lower()

else:

return '_'.join(carstr.split(' ')[:2]).replace('-','').lower()

# using google sheets data downloaded to tsv

df_wt = (pd.read_csv("/tmp/ev_weight.tsv", sep='\t'))

df_real = (pd.read_csv("/tmp/ev_range.tsv", sep='\t')

.merge(df_wt, on='Car')

.rename(columns={'Total':'weight'})

.assign(tire_size=lambda df: df["Wheel front"].str.extract('\-(\d\d)'))

.dropna(subset=['Wh/km', 'tire_size', 'weight'])

.assign(tire_size=lambda df: df.tire_size.astype(int))

.assign(Temp=lambda df: df.Temp.str.replace(u"\u2212",'-').astype(float))

)

df_clean = (

df_real

.assign(car = lambda df: df.Car.apply(get_car))

.assign(Whk = lambda df: df['Wh/km'])

.assign(ton = lambda df: df.weight/1000)

.assign(wet = lambda df: (df.Surface=="Wet").astype(int))

.assign(dgC = lambda df: df.Temp)

.assign(tir = lambda df: (df.tire_size-14).astype(float))

.assign(spd = lambda df: (df.Speed==120).astype(int))

.loc[lambda df: ~df.car.str.startswith('mitsubishi')]

.loc[lambda df: ~df.car.str.startswith('maxus')]

[["Whk", "car", "tir", "ton", "wet", "spd", "dgC"]]

.dropna()

)

df_real.to_csv("/tmp/df_ev_range.csv")

df_clean.to_csv("/tmp/df_ev_range_clean.csv")

prior_car = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=100, sigma=50)

prior_ton = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=50, sigma=20)

prior_dgC = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=-1, sigma=2)

prior_wet = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=10, sigma=20)

prior_tir = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=2, sigma=5)

prior_spd = Prior('StudentT', nu=3, mu=50, sigma=30)

model_clean = Model(df_clean)

print(f"{len(df_clean)} samples")

res_clean = model_clean.fit(

'Whk ~ 0 + ton + dgC + tir + spd + wet',

group_specific=["1|car"],

categorical=['car', 'wet', 'spd'],

priors = {'car': prior_car, "ton": prior_ton, "dgC": prior_dgC,

"wet": prior_wet, "tir": prior_tir, "spd": prior_spd},

draws=2000, chains=4

)

car_means = res_clean.posterior['1|car'].mean(dim=("chain", "draw"))

res_clean.posterior = res_clean.posterior.sortby(-car_means)

g = az.plot_forest(res_clean.posterior, kind='ridgeplot', var_names=['1|car'], combined=True,

colors='#eeeeee', hdi_prob=0.999);

g[0].set_xlabel('Wh/km');

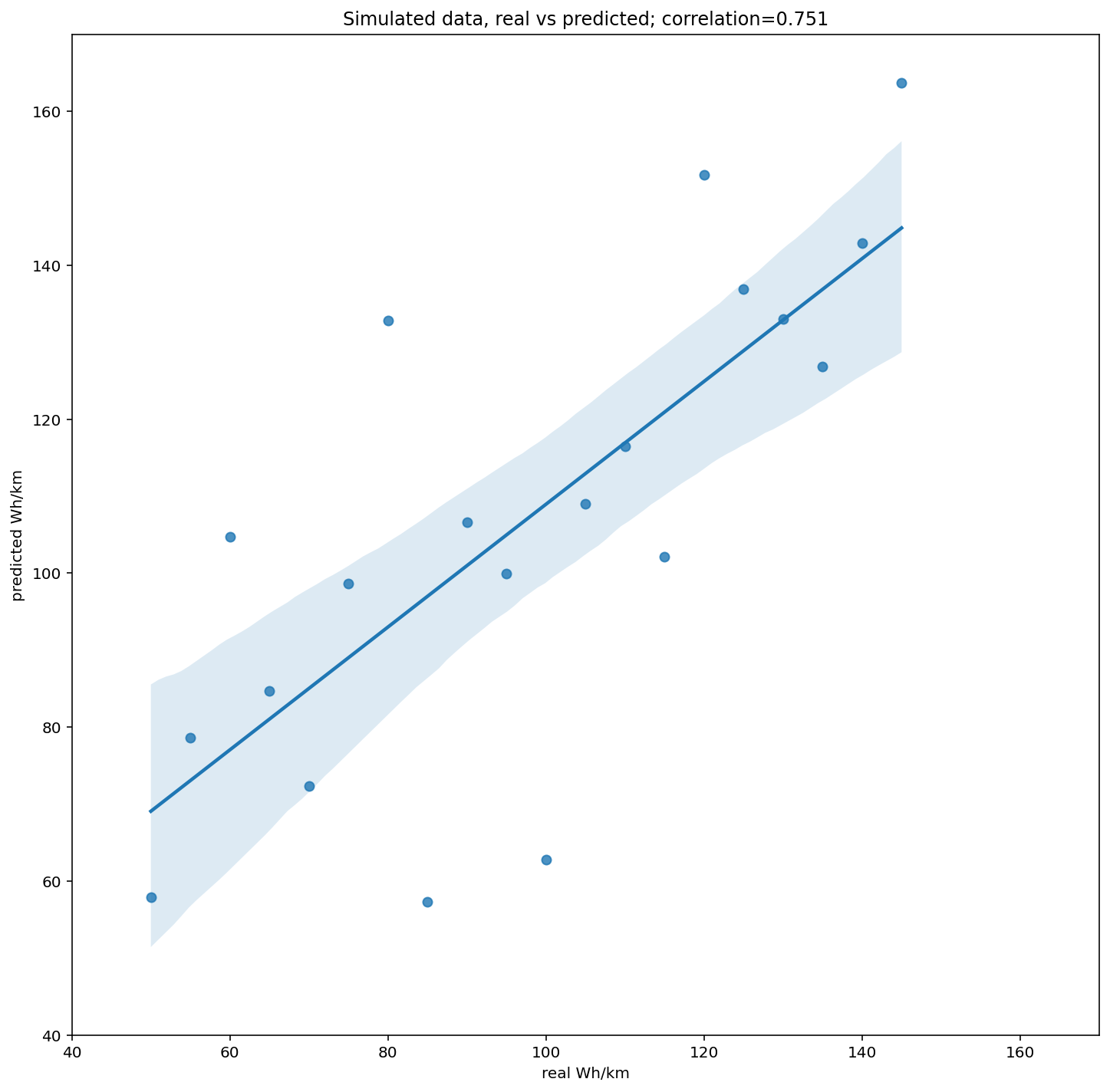

Results

There is plenty of overlap in these posteriors, but they do show that e.g., Tesla, Hyundai and Porsche seem to have good base efficiency, while Jaguar, Audi, and Volvo appear to have poor efficiency.

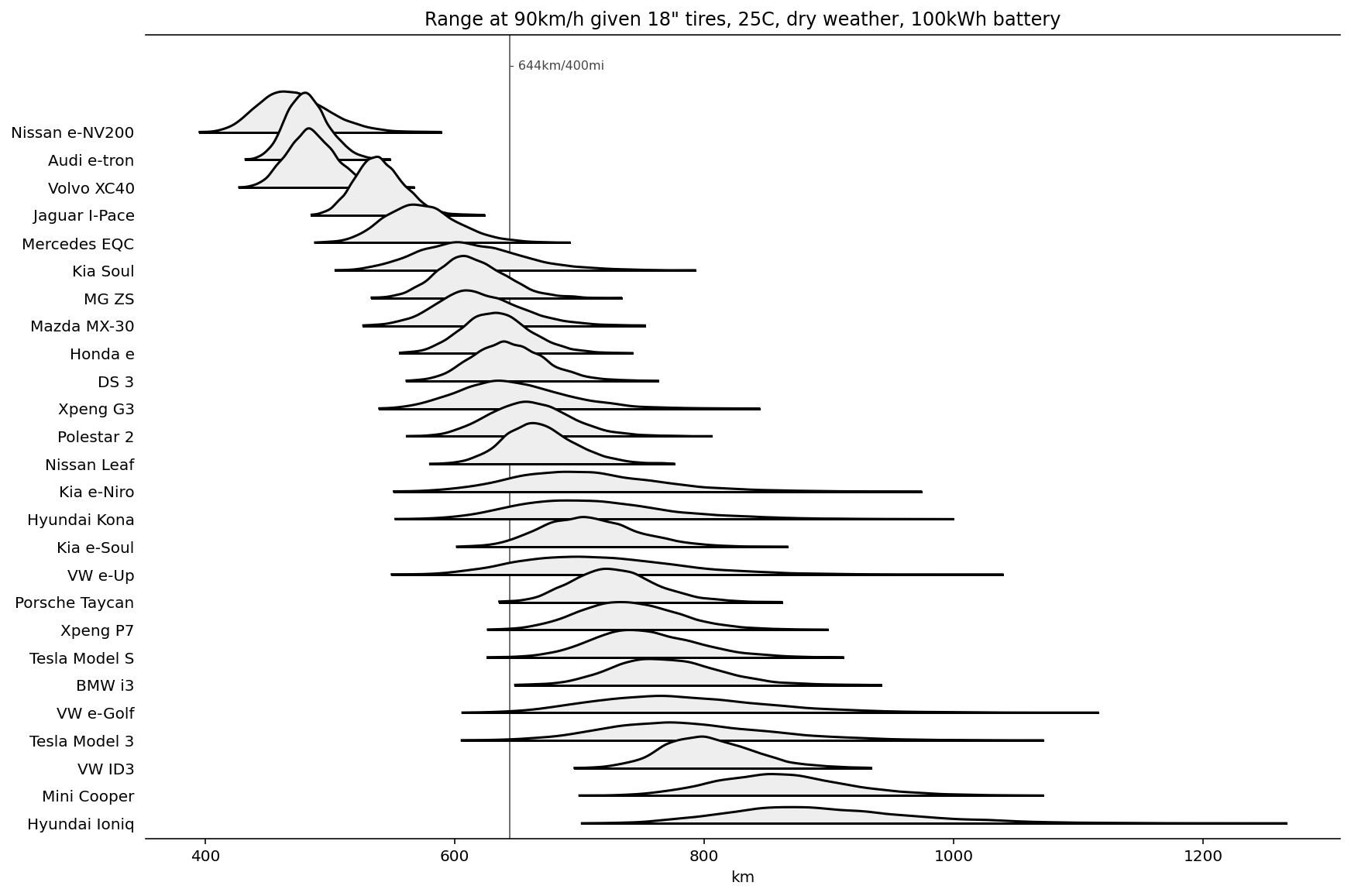

We can also look at the estimated range for each car at 90km/h given dry weather, 18" tires, 25C and a 100kWh battery. (Caveat: I don't know how to adjust the range for additional battery weight, so there is an unfair advantage for cars with small batteries.) Still, these results show that once battery density increases a bit, several cars may be able to hit the 400mi/644km range.

It was also interesting to discover the contributions of other factors, though the numbers below are just +/-1 standard deviation and should be taken with plenty of salt:

- traveling at 120km/h adds 60–70 Wh/km compared to 90km/h;

- each degree C colder adds 0.5–1.25 Wh/km;

- each ton weight adds 20–40 Wh/km;

- each inch of tire adds 2–6 Wh/km;

- wet weather adds 10–20 Wh/km.

My main takeaways were that speed is extremely important (drag), tire size was less important than I had guessed based on the Porsche example, but wet weather was more important than I had guessed (maybe equivalent to carrying an extra ton??)

As always, there are things I could improve in the model, especially with more data: better chosen, bounded priors; more prior and posterior predictive checks (I had some issues here); checking for interactions (e.g., wet*dgC); perhaps some multiplicative effects (e.g., wet weather reduces efficiency by 5% instead of subtracting 10 Wh/km). I could also maybe predict optimal conditions for maximum range, though the current model would say on the surface of the sun with 0 inch tires.

I might come back to it when the database has grown a bit, but I am pretty satisfied with these results for now.

data / brms code

If anyone wants to rerun/improve upon the above, I put all the data here: ev_range.tsv, ev_weight.tsv, df_ev_range.csv, df_ev_range_clean.csv, df_ev_range_sim.csv. This could be a pretty nice dataset for teaching.

To validate (or at least reproduce) the model above, I ran the following R code. The results were virtually identical.

library('brms')

df_clean = read.csv("/tmp/df_ev_range_clean.csv")

priors = c(set_prior("student_t(3,100,50)", class = "b", coef = paste("car", sort(unique(df_clean$car)), sep="")),

set_prior("student_t(3,50,20)", class = "b", coef = "ton"),

set_prior("student_t(3,-1,2)", class = "b", coef = "dgC"),

set_prior("student_t(3,10,20)", class = "b", coef = "wet"),

set_prior("student_t(3,2,5)", class = "b", coef = "tir"),

set_prior("student_t(3,50,30)", class = "b", coef = "spd")

)

res_clean = brm(

Whk ~ 0 + ton + dgC + tir + car + spd + wet + (1|car),

data=df_clean,

chains = 4,

iter = 3000,

cores = 4,

prior=priors,

control = list(adapt_delta = 0.95, max_treedepth = 20))