I have written about protein binder design a few times now (the Adaptyv competition; a follow up). Corin Wagen recently wrote a great piece about protein–ligand binding. This purpose of this post is to review how well protein binder design is working today, and point out some interesting differences in model performance that I do not understand.

Protein design

There are two major types of protein design:

- Design a sequence to perform some task: e.g., produce a sequence that improves upon some property of the protein

- Design a structure to perform some task: e.g., produce a protein structure that binds another protein

There is spillover between these two classes but I think it's useful to split this way.

Sequence models

Sequence models include open-source models like the original ESM2, ProSST, SaProt, and semi-open or fully proprietary models from EvolutionaryScale (ESM3), OpenProtein (PoET-2), and Cradle Bio. The ProteinGym benchmark puts ProSST, PoET-2 and SaProt up near the top.

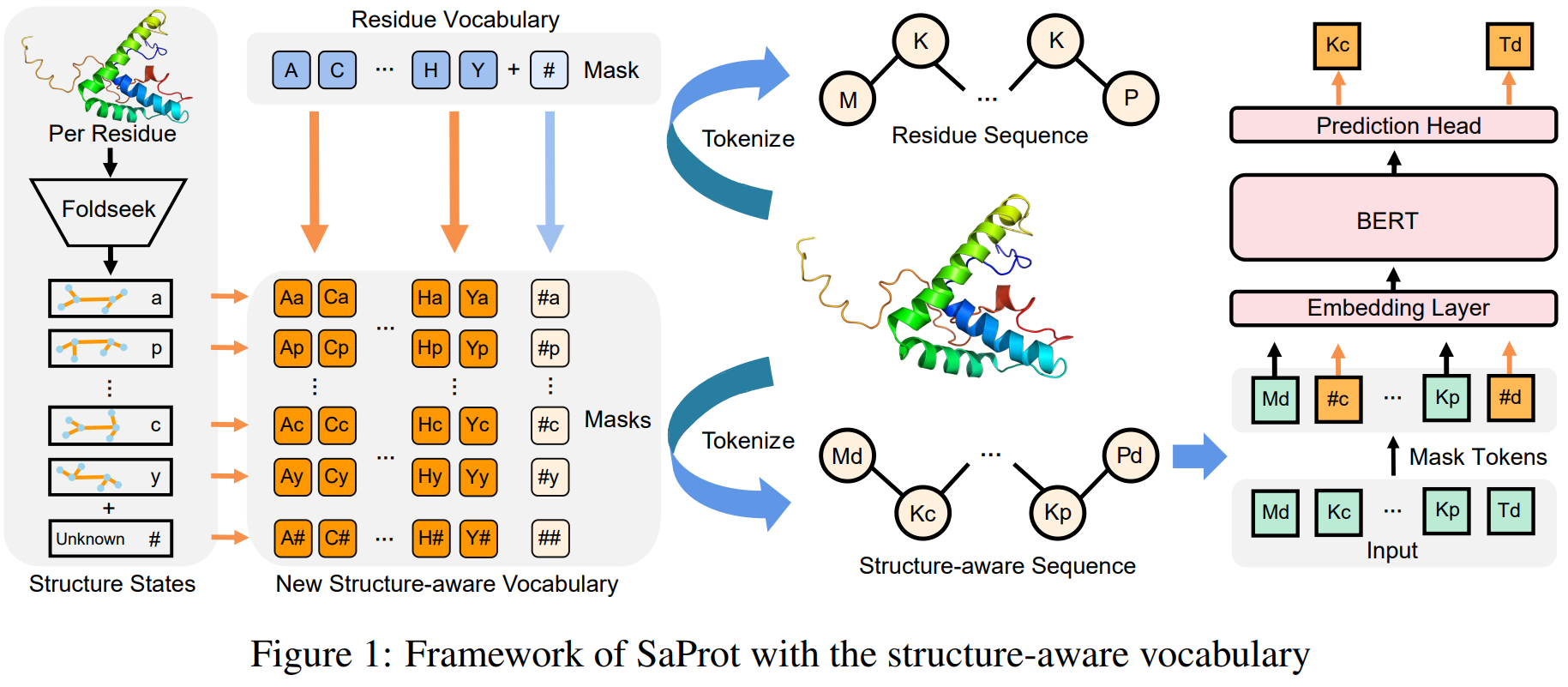

Many of the recent sequence-based models now also include structure information, represented as a parallel sequence, with one "structure token" per amino acid. This addition seems to improve performance quite a lot, allows sequence models to make use of the PDB, and — analogously to Vision Transformers — blurs the line between sequence and structure models.

SaProt uses a FoldSeek-derived alphabet to encode structural information

The most basic use-case for sequence models is probably improving the stability of a protein. You can take a protein sequence, make whatever edits your model deems high likelihood, and this should produce a sequence that retains the same fold, but is more "canonical", and so may have improved stability too.

An elaboration of this experiment is to find some data, e.g., thermostability for a few thousand proteins, and fine-tune the original language model to be able to predict that property. SaProtHub makes this essentially push-button.

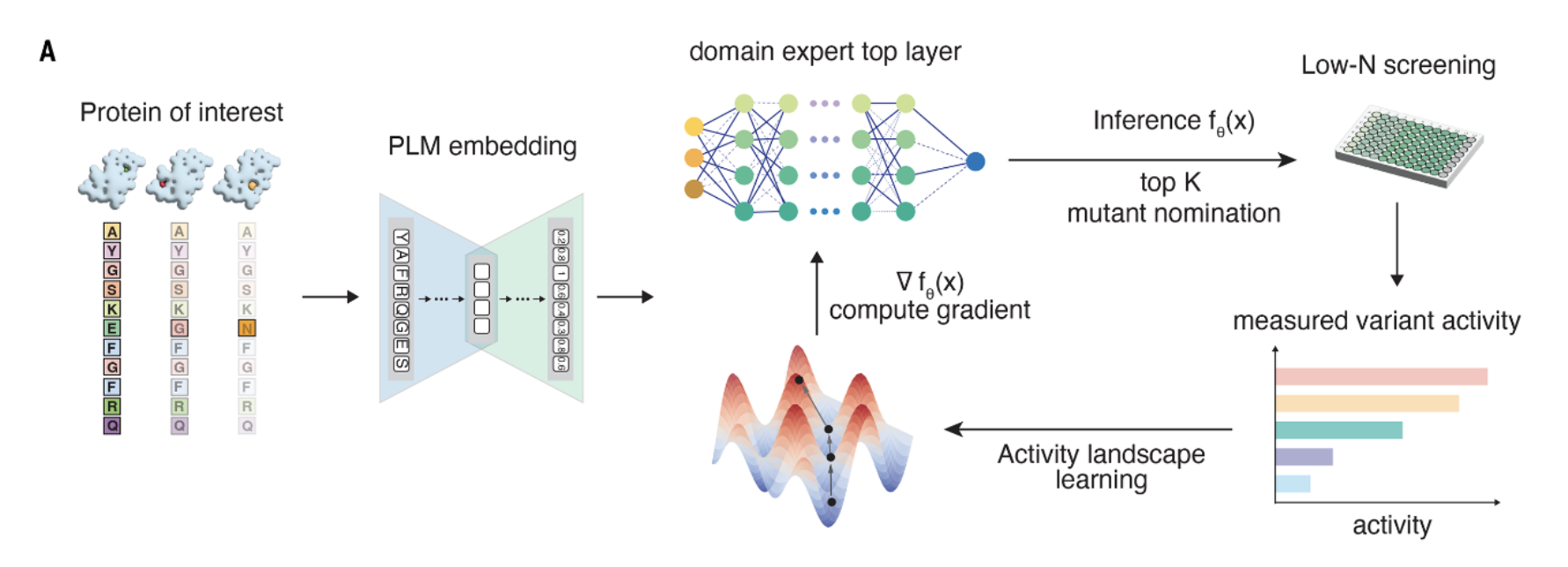

A further elaboration is doing active learning, where you propose edits using your model, generate empirical data for these edits (e.g., binding affinity), and go back and forth, hopefully improving performance each iteration. For example, EVOLVEpro, Nabla Bio's JAM (which also uses structure), and Prescient's Lab-in-the-loop. These systems can be complex, but can also be as simple as running regressions on the output of the sequence models.

EvolvePro's learning loop

Sequence-based models are a natural fit to these kinds of problems, since you can easily edit the sequence but maintain the same fold and function. Profluent and other companies make use of this ability by producing patent-unencumbered sequences like OpenCRISPR.

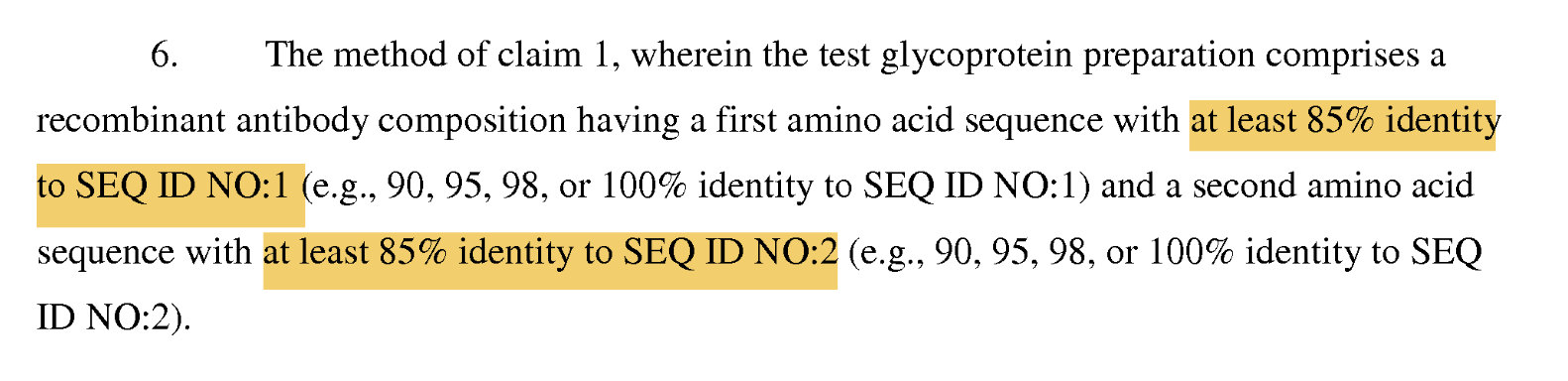

This is especially enabling for the biosimilars industry. Many biologics patents protect the sequence by setting amino acid identity thresholds. For example, in the Herceptin/trastuzumab patent they protect any sequence >=85% identical to the heavy (SEQ ID NO: I) or light chain (SEQ ID NO: II).

Excerpt from the main trastuzumab patent

Patent attorneys will layer as many other protections on top of this as they can think of, but the sequence of the antibody is the primary IP. (Tangentially, it is insane how patents always give examples of numbers greater than X. Hopefully, the AIs that will soon be writing patents won't do this.)

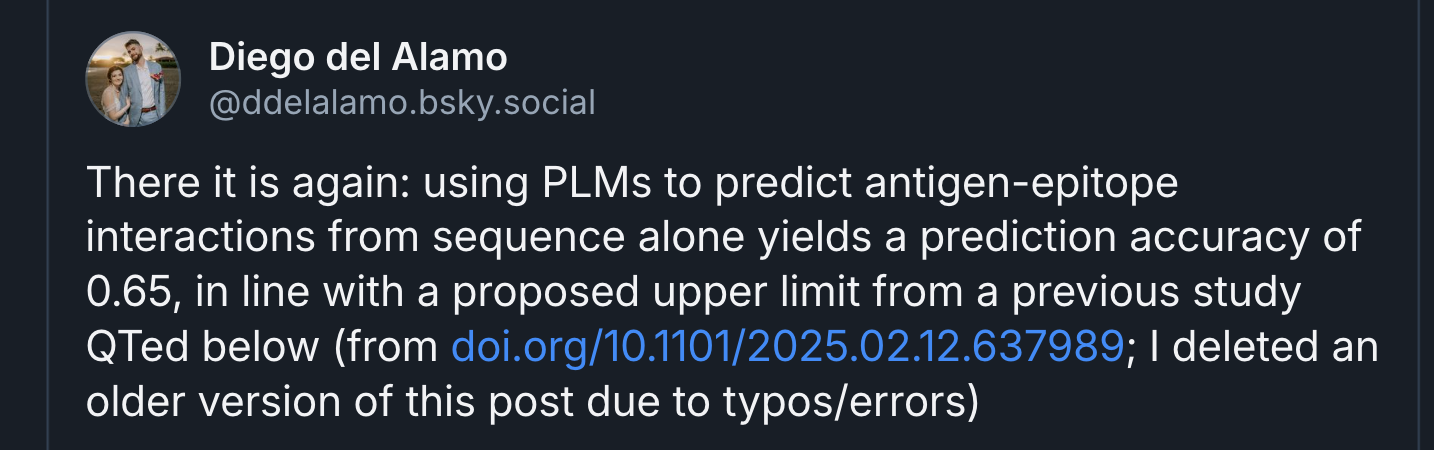

For binder design, sequence models appear to have limits. Naively, since you do not know the positions of the atoms, then unless you are apeing known interaction motifs, you would assume binder design should be difficult?

Diego del Alamo points out apparent limits in the performance of sequence models for antibody design

Structural models

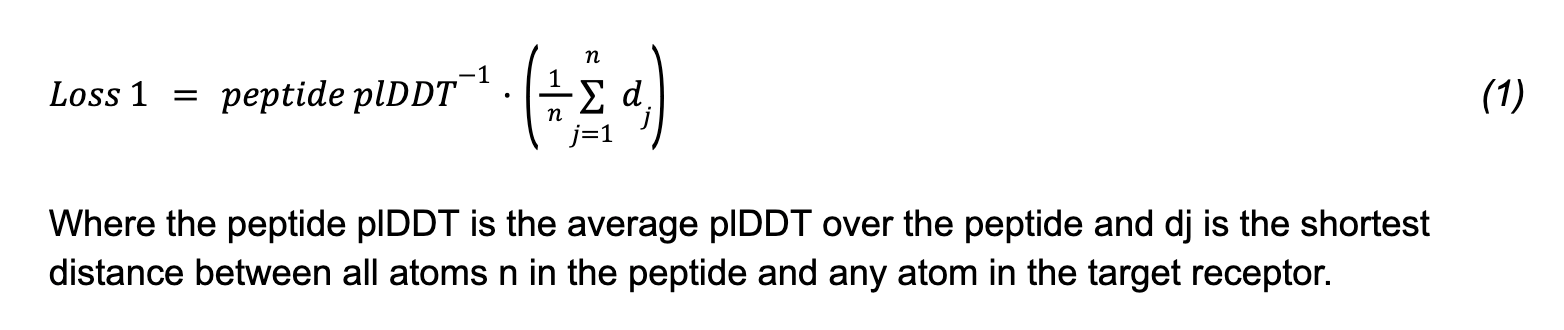

Structural models include the original RFdiffusion and the recently released antibody variant RFantibody from the Baker lab, RSO from the ColabDesign team, BindCraft, EvoBind2, foldingdiff from Microsoft, and models from startups like Generate Biomedicines (Chroma), Chai Discovery, and Diffuse Bio. (Some of these tools are available on my biomodals repo).

Structural models are trained on both sequence data (e.g., UniRef) and structure data (PDB), but they deal in atom co-ordinates instead of amino acid strings. That difference means diffusion-style models dominate here over the discrete-token–focused transformers.

There are two major classes of structural models:

- Diffusion models like RFdiffusion and RFantibody

- AlphaFold2-based models like BindCraft, RSO, and EvoBind2

The success rates of RFdiffusion and RFantibody are not great. For some targets they achieve a >1% success rate (if we define success as finding a <1µM binder), but in other cases they nominate thousands of designs and find no strong binder.

An example from the RFantibody paper showing a low success rate

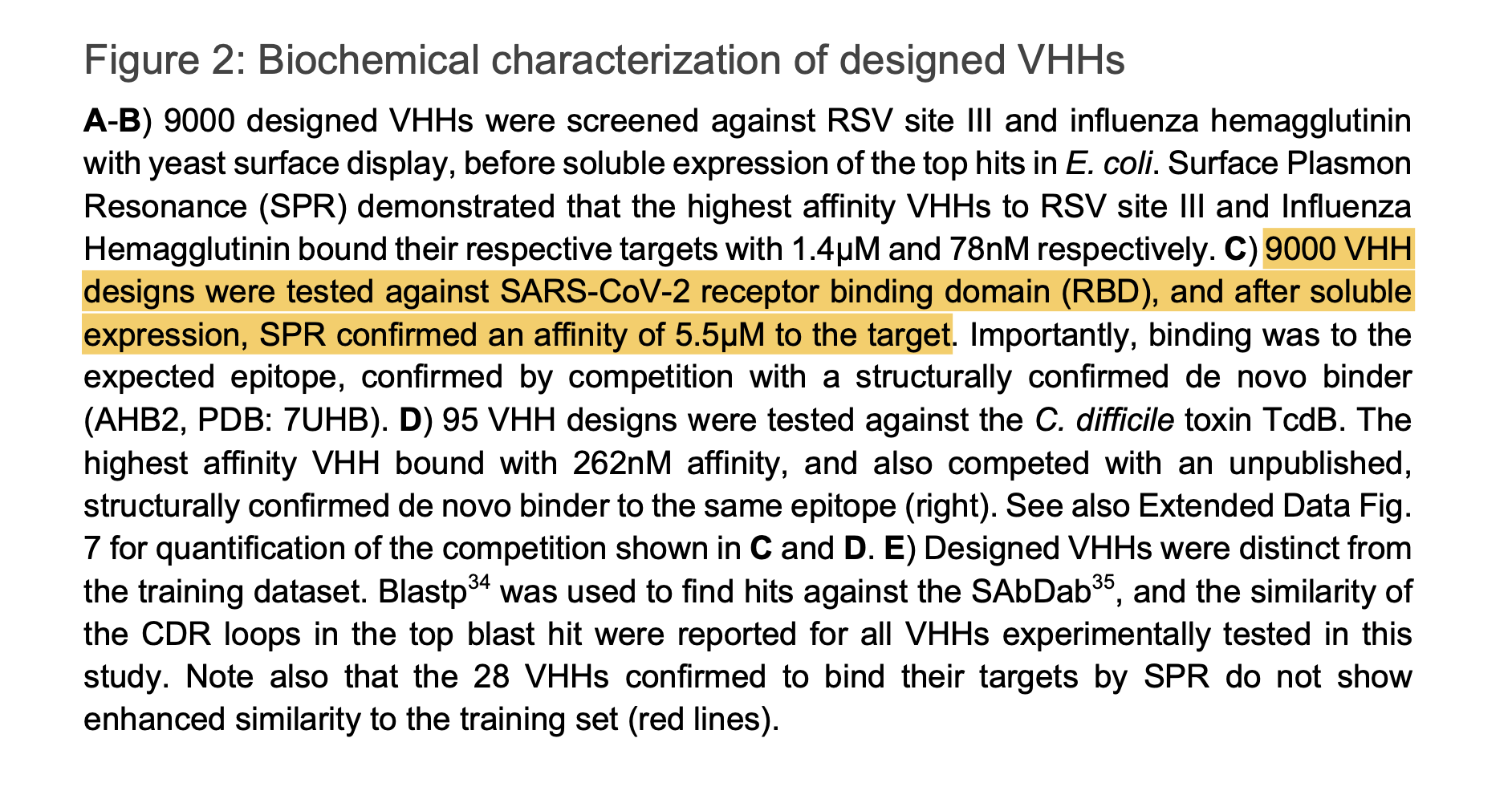

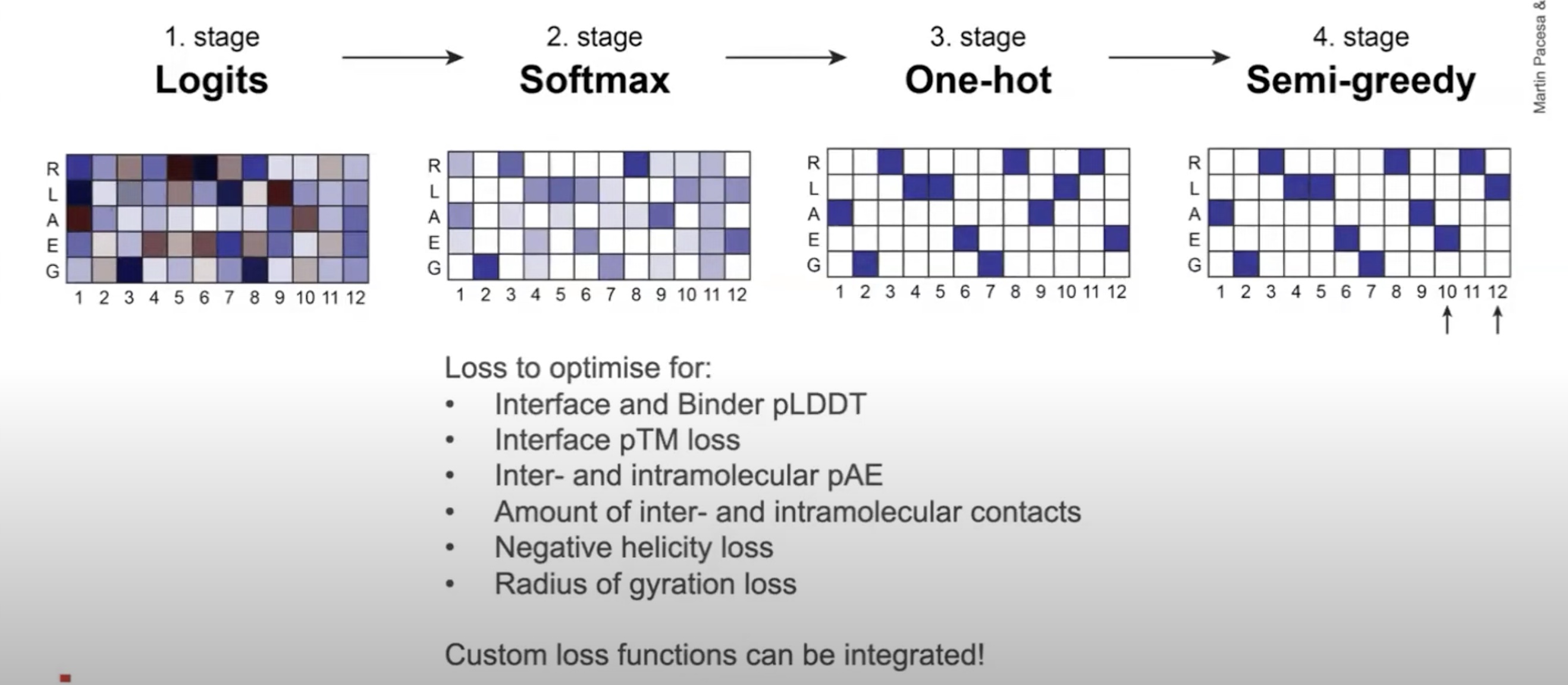

BindCraft and RSO are two similar methods that produce minibinders (small-ish non-antibody–based proteins) and rely on inverting AlphaFold2 to turn structure into sequence. EvoBind2 produces cyclic or linear peptides, and also relies heavily on an AlphaFold confidence metric (pLDDT) as part of its loss.

BindCraft (top) and EvoBind2 (bottom) have similar loss functions that rely on AF2's pLDDT and intermolecular contacts

Even though these AF2-based models work very well, one non-obvious catch is that you cannot take a binding pose and get AlphaFold2 to evaluate it. These models can generate binders, but not discriminate binders from non-binders. In the EvoBind2 paper, they found that "No in silico metric separates true from false binders", which means the problem is a bit more complex than just "ask AF2 if it looks good".

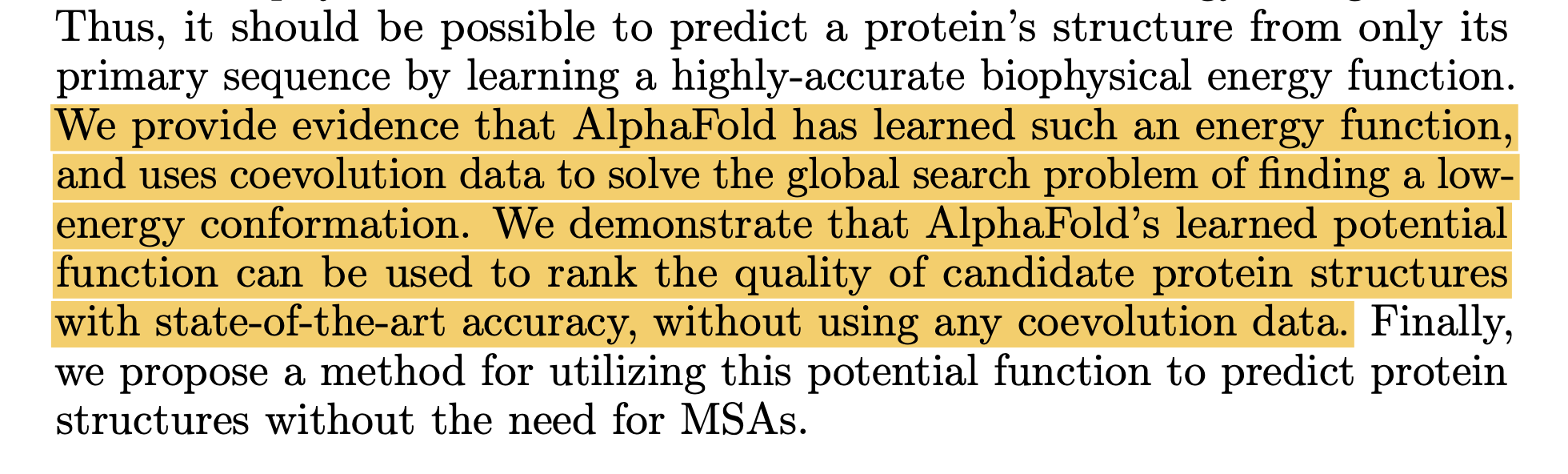

According to the AF2Rank paper, the AF2 model has a good model of the physics of protein folding, but may not find the global minimum. The MSAs' job is to help focus that search. This was surprising to me! The protein folding/binding problem is more of a search problem than I realized, which means more compute should straightforwardly improve performance by simply doing more searching. This is also evidenced by the AlphaFold 3 paper, where re-folding antibodies 1000 times led to improved prediction quality.

Excerpt from the AF2Rank paper (top), and a tweet from Sergey Ovchinnikov (bottom)

explaining the primacy of sequence data in structure prediction

RFdiffusion/RFantibody vs BindCraft/EvoBind2

The main comparison I wanted to make in this post is between RFdiffusion/RFantibody vs BindCraft and EvoBind2.

These are all recently released, state-of-the-art models from top labs. However, the difference in claimed performance is pretty striking.

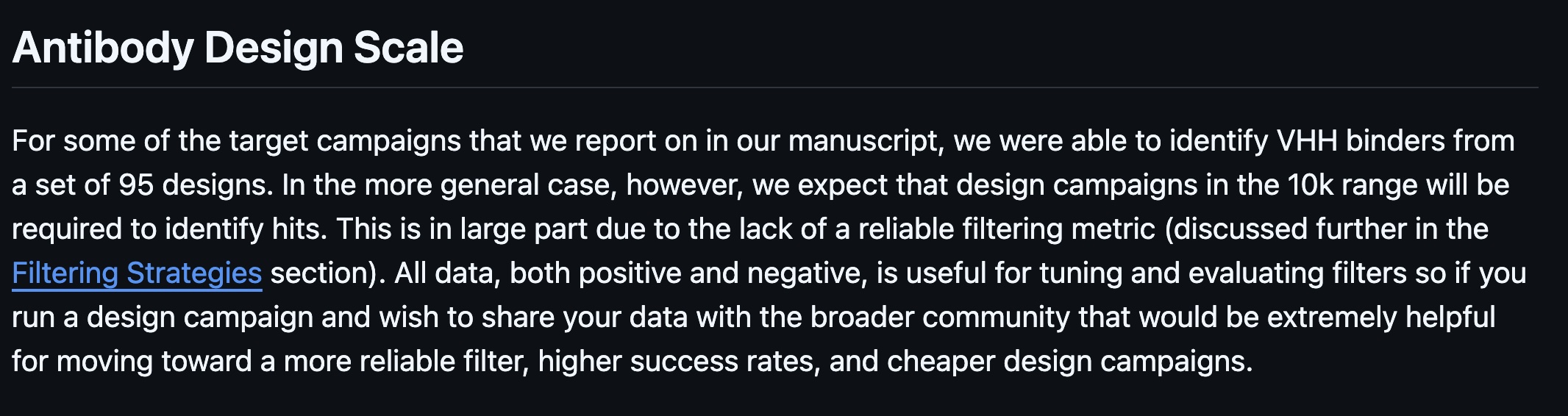

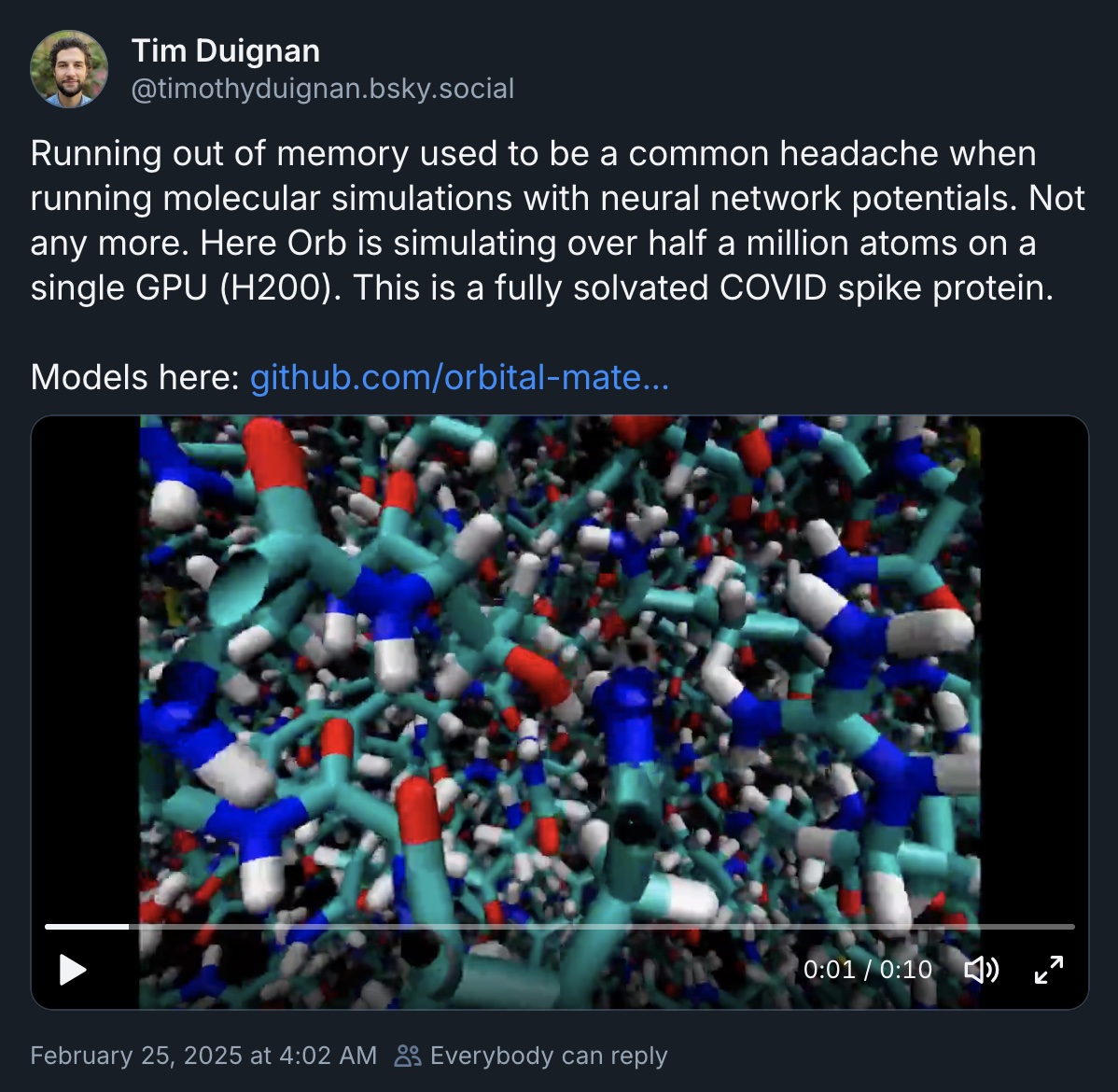

While the RFdiffusion and RFantibody papers caution that you may need to test hundreds or even thousands of proteins to find one good binder, the BindCraft and EvoBind2 papers appear to show very high success rates, perhaps even as high as 50%. (EvoBind2 only shows results for one ribonuclease target but BindCraft includes multiple).

Words of caution from the RFantibody github repo (top)

and BindCraft's impressive results for 10 targets (bottom)

There is no true benchmark to reference here, but I think under reasonable assumptions, BindCraft (and arguably EvoBind2) achieve a >10X greater success rate than RFdiffusion or RFantibody. The Baker lab is the leading and best resourced lab in this domain, so what accounts for this large difference in performance? I can think of a few possibilities:

- RoseTTAFold2 was not the best filter for RFantibody to use, and switching to AlphaFold3 would improve performance. This is plausible, but it is hard to believe that is a 10X improvement.

- Antibodies are just harder than minibinders or cyclic peptides. Hypervariable regions are known to be difficult to fold, since they do not have the advantage of evolutionary conservation. However, RFdiffusion also produces minibinders, so this is not a satisfactory explanation.

- BindCraft and EvoBind2 are testing on easier targets. There is likely some truth to this. Most (but not all) examples in the BindCraft paper are for proteins with known binders; EvoBind2 is only tested against a target with a known peptide binder. However, most of RFantibody's targets also have known antibodies in PDB.

- Diffusion currently just does not work as well as AlphaFold-based methods. AlphaFold2 (and its descendants, AF3, Boltz, Chai-1, etc.) have learned enough physics to recognize binding, and by leaning on this ability heavily, and filtering carefully, you get much better performance.

What comes next?

RFdiffusion and RFantibody are arguably the first examples of successful de novo binder design and antibody design, and for that reason are important papers. BindCraft and EvoBind2 have proven they can produce one-shot nanomolar binders under certain circumstances, which is technically extremely impressive.

However, if we could get another 10X improvement in performance, then I think these tools are being used in every biotech and research lab. Some ideas for future directions:

- More compute: One of the interesting things about BindCraft and EvoBind2 is how long they take to produce anything. In BindCraft's case, it generates a lot of candidates, but has a long list of criteria that must be met. One BindCraft run will screen hundreds or thousands of candidates and can easily cost $10+. Similary, EvoBind2 can run for 5+ hours before producing anything, again easily costing $10+. This approach of throwing compute at the problem may be generally applicable, and may be analogous to the recently successful LLM reasoning approaches.

- Combine diffusion and AlphaFold-based methods: I have no specific idea here, but since they are quite different approaches, maybe integrating some ideas from RFdiffusion into EvoBind2 or BindCraft could help.

- Combine sequence models and structure models: There is already a lot of work happening here, both from the sequence side and structure side. In the simplest case, the output of a sequence model like ESM2 could be an independent contributor to the loss of a structure model. At the very least, this could help filter out structures that do not fold.

- Neural Network Potentials: Neural Network Potentials are an exciting new tool for molecular dynamics (see Duignan, 2024 or Barnett, 2024). Achira just got funded to work on this, and has several of the pioneers of the field on board. Semi-open source models like orb-v2 from Orbital Materials are being actively developed too. The amount of compute required is prohibitive right now, but even a short trajectory could plausibly help with rank ordering binders, and would be independent of the AF2 metrics.

Tweet from Tim Duignan at Orbital Materials